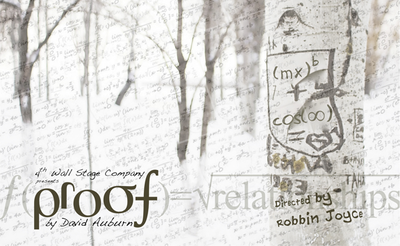

Proof

January – February 2013

Director: Robbin Joyce

Sound Design: Robbin Joyce and David Anderson

Lighting Design: David Anderson

Photography: Frank Bartucca

Stage Managers: Ginny Sears

Cast:

Fred D’Angelo…..Robert

Brianna Gardell…..Catherine

Sean Gardell…..Hal

Aimee Kewley…..Claire

Theater Review:

By Paul Kolas TELEGRAM & GAZETTE REVIEWER

“4th Wall’s ‘Proof’ excels in the act of seeking truth”

NORTHBRIDGE — David Auburn’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Proof” has a lot less to do with math than it does with the theme of trust and fear of madness, both of which were addressed with riveting intensity in 4th Wall Stage Company’s exhilarating production Saturday evening.

It’s been said that genius and madness share two sides of the same coin, and it’s a blessing-curse conundrum that inhabits Robert (Fred D’Angelo), a world-class mathematician who went, as he calls it, “bughouse.” His daughter, Catherine (Briana Gardell), has given up her own ambitions in the field to care for her father, fearful that she has inherited his?mental instability.

Set entirely on the back porch of the family home in Chicago, the play’s opening scene does not make it immediately apparent that it is a fantasized conversation between Catherine and her just-deceased father. He’s trying to rally her out of her unmotivated stupor, on the eve of her 25th birthday, exhorting her to get out of bed before noon and do something with her life. After all, she’s somewhat of a math whiz herself.

She frets about knowing whether she’s crazy or not, and Robert comforts her with the notion that crazy people don’t ask themselves if they’re crazy. Catherine’s older sister, Claire (Aimee Kewley), is flying in from New York for Robert’s funeral, also concerned that Catherine is cursed with mad genius disorder and wants her to come back to New York with her for therapy.

Hal (Sean Gardell), one of Robert’s former students, comes snooping around the house looking through Robert’s pile of notebooks for potentially significant breakthroughs Robert may have discovered during a nine-month remission of lucidity. When Hal finds a ground-breaking proof about prime numbers poking through the mountain of gibberish scribbled in Robert’s notebooks, the proof’s authenticity and authorship trigger a dynamic interplay that is emotionally and intellectually enervating.

One can abhor math and still admire what director Robbin Joyce and her excellent cast bring to the bracing mix of feelings and ideas that pervade “Proof.” Briana Gardell is superlative as Catherine, calling up manifold emotions at will. One moment she can appear on the brink of a nervous breakdown, but too listless to follow through on it, a pale, fatigued portrait of self-immolating resignation. Then she’ll flash an incandescent smile that lights up the theater, when Hal rouses her out of her dormant malaise with attention beyond the academic.

When their relationship is put to the test in the play’s trust-issue moments, one might well surmise that the Gardells draw on their real-life partnership to bring such passionate, biting realism to the scene.

Sean Gardell, wearing a variety of colorful T-shirts throughout, is an endearing, scruffy geek as Hal, employing all sorts of lovable, awkward, nervous tics and gestures in his performance. He makes Hal an intellectually curious, appealing puppy dog.

Kewley is splendid as well-meaning, stridently pragmatic Claire. She thinks she knows what’s best for her sister, but Catherine will have none of it. Their final encounter is a furiously acted clash of wills, Claire insisting that New York will make Catherine feel alive again, Catherine mocking her with visions of attending Broadway musicals and afternoons at Lincoln Center.

D’Angelo is quite affecting in the role of Robert, imbuing him with a fragile, sad, quirky quality that seems just right for a man with a brilliant mind gone awry. In flashback, it’s heartbreaking when he exclaims with joy to Catherine that he’s back in genius mode, ready to reach new glorious heights of productivity. He eagerly gives Catherine his notebook, to show her what he’s written down, but the stricken look on her face tells us otherwise. It’s also wrenching to watch Robert break down in tears when he realizes he’s forgotten Catherine’s 21st birthday.

Joyce directs with a steady hand, giving her actors room to breathe without letting our attention divert for a second. If you want proof that first-rate community theater is rampant in Central Massachusetts, look no further.

Uncle Vanya

May 2014

Director: Frank Bartucca

Assistant Director: Barbara Guertin

Sound Design: Frank Bartucca, Barbara Guertin, Kyle Lampe

Lighting Design: David Anderson

Photography: Frank Bartucca

Stage Manager: Steve Robsky

Cast:

David Anderson…..Uncle Vanya

Frank Bartucca…..The Professor

Melissa Earls…..Yelena

Nancy Hilliard…..Nanny

Allison Matteodo…..Sofya

Christopher O’Connor…..Telegin

Steve Robsky…..Workman

Alice Springer…..Mariya

Sean Stanco…..Dr. Astrov

David Mamet’s adaptation of Uncle Vanya is precise and clear, its language thoroughly modern yet not colloquial, and respects the dignity of Chekhov’s finely etched characters. Chekhov, and Mamet, lead us into the contemporary world, into each life’s mixture of yearning and ennui, laughter and reflection, failure and accomplishment, hope and affection. First published during the reign of Czar Nicholas the II, the action of Uncle Vanya takes place on a rural estate during the visit of a retired Professor and his young, beautiful wife, both of whom are supported in their urban lifestyle by the labor of the estate’s permanent residents, who include the Professor’s daughter by his (deceased) first wife and his first wife’s brother.

Theater Review:

By Paul Kolas TELEGRAM & GAZETTE REVIEWER

“4th Wall’s ‘Proof’ excels in the act of seeking truth”

NORTHBRIDGE— There is community theater, and then there is 4th Wall Stage Company’s transcendent, coruscating, ultimately cleansing production of David Mamet’s adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya,” which takes things to an entirely higher level of classification and regard.

Friday evening’s performance could hold its head high on a Boston or New York stage, a personal evaluation which renders a star rating system both problematic and irrelevant. Suffice it to say that director Frank Bartucca, who also addresses the role of the elderly Professor Serebryakov with commanding pomposity, is fearless when it comes to taking on major works by such playwrights as Eugene O’Neill and Sam Shephard. Add Anton Chekhov to that vaunted list.

It’s quite remarkable how a play about, among other things, boredom, could be so riveting. It’s a contradiction brought vibrantly to life by a cast thrillingly attuned to the thematic palette of failure, regret, yearning, passion, resentment, rage, forgiveness, and hope that Chekhov presents to us.

Taking place at Serebryakov’s estate in rural Russia in the late 1800s, the daily routine of its inhabitants is upended by the return of The Professor to the estate, after a long absence, with his beautiful young wife, Yelena (Melissa Earls). His health is declining, and the county doctor, Astrov (Sean Stanco) has been summoned to cure the ailing Professor.

Vanya (David Anderson) has been in charge of caring for the estate for 25 years, and seeing Yelena again stirs his love for her. The admiration Vanya once had for Serebryakov, when he was married to Vanya’s late sister, Vera, has now curdled into seething anger. He feels he’s wasted his life, missing an opportunity to marry Yelena when he had a chance 10 years earlier, and fuming over the fact that she’s married a much older man who now regards Vanya, who once believed he would achieve greatness under Serebryakov’s mentorship, as a nobody.

Whatever you may have planned for the remainder of this weekend, or the next, do your best to make time to see what Anderson brings to the role of Vanya. As marvelous as he was as James Tyrone Jr. in 4th Wall Stage Company’s superb production of O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” his performance here is a marathon of emotional range. He’s heartbreaking, teasing, hurtful, frightening, clownish, unruly, and altogether electrifying. There are moments when one feels that both the actor and the character are out of control, like Joaquin Phoenix’s Freddie Quell in Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master.”

When Vanya unleashes his rage against Serebryakov’s sneering evaluation of his failed life, Anderson brings it on with a volcanic tantrum that is unsettling in its realism, accusing the Professor of ruining his life, depriving him of chance to become another “Schopenhauer, a Dostoevsky.” At the other end of Anderson’s vast emotional spectrum is the empathy he elicits when Yelena rejects his “fall head over heels in love with some water-sprite” advances.

Earls gives what may well be her most refined and fully realized performance to date as Yelena, a lovely composition of languid sadness and resignation. She tells Allison Matteodo’s Sonya (Serebryakov’s daughter from his first marriage and Vanya’s niece), that she may have married the Professor for love, but in retrospect, it wasn’t real love.

When she confesses to Sonya that she’s unhappy, Matteodo beams with a misery-loves-company smile. Sonya will take whatever compensation she can get from the fact that Yelena brings her the disheartening confirmation that Astrov cannot requite her love for him. Matteodo embues the “plain-looking” Sonya with a touching, eager sweetness, right up to her play-concluding, consoling “We shall rest!” speech to her Uncle Vanya.

Stanco brings a persuasive, masculine ardor to the role of Astrov, in keeping with the Mamet undertow coursing through Chekhov’s work, delivering Astrov’s diatribe about the demise of the Russian forest with the fervor of an impassioned environmentalist. And he and Earls bring thwarted heat to Astrov and Yelena’s mutual attraction.

Nancy Hilliard is warmly embracing as the enduring, wise, religious Marina, the estate’s nanny, who, unlike Serebryakov, keeps her aging aches and pains to herself. Christopher O’Connor portrays Telegin, nicknamed “Waffles” for his pock-marked face, with the sort of rustic, big-hearted appeal befitting a poor landowner. As Vanya’s mother, Mariya, Alice Springer effectively imparts her diminished ability to influence family conflict. Mariya contents herself with reading pamphlets and doting on her son-in-law, defending him against Vanya’s acrimony.

As if Anderson doesn’t have enough to do, he’s also responsible for the production’s subliminal lighting design of tree branches set against an azure sky. With the added intimacy created by converting the Singh Performance Center’s conventional platform seating into a theater-in-the-round format, you will feel even more immersed in this brilliant production.